Update below

In its bold ‘Response to President Xi Jinping‘ of China, the New York Times editorial board takes a stand:

The Times has no intention of altering its coverage to meet the demands of any government — be it that [sic] of China, the United States or any other nation. Nor would any credible news organization. The Times has a long history of taking on the American government, from the publication of the Pentagon Papers to investigations of secret government eavesdropping.

But despite the Times‘ claims to the contrary, this, like most rules, must come with an American Exception. This is a brazen whitewashing of the very type of stories the New York Times is known for withholding to meet the demands of the United States government: secret government eavesdropping. As has been well documented, the Times sat on James Risen’s and Eric Lichtblau’s revelation that the Bush administration was illegally wiretapping American citizens without warrants for more than a year, publishing ‘Bush Lets U.S. Spy On Callers Without Courts’ on December 16, 2005.

Mostly for my own edification, some history:

In that original story, the Times admits:

The White House asked The New York Times not to publish this article, arguing that it could jeopardize continuing investigations and alert would-be terrorists that they might be under scrutiny. After meeting with senior administration officials to hear their concerns, the newspaper delayed publication for a year to conduct additional reporting. Some information that administration officials argued could be useful to terrorists has been omitted.

As FAIR wrote at the time, in ‘The Scoop That Got Spiked,’

The reasoning is absurd on its face. As Times executive editor Bill Keller noted in a statement released on December 16 explaining his decision to publish the story, “The fact that the government eavesdrops on those suspected of terrorist connections is well-known.” But this was as obvious a year ago as it is today. As for the government’s spying being “jeopardized,” placing illegal and unconstitutional programs in jeopardy is the whole point of the First Amendment.

When the newspaper’s own public editor at the time, Byron Calame, tried to investigate that withholding, he reported that he was “stonewall[ed],” saying, “I have had unusual difficulty getting a better explanation for readers, despite the paper’s repeated pledges of greater transparency.”

Calame even floated the implication that the Times withheld the story for political reasons (and followed up on that question later that year):

If no one at The Times was aware of the eavesdropping prior to the election, why wouldn’t the paper have been eager to make that clear to readers in the original explanation and avoid that politically charged issue? The paper’s silence leaves me with uncomfortable doubts.

Two years later, one of the original reporters, Eric Lichtblau, confirmed the timing: “For 13 long months, we’d held off on publicizing one of the Bush administration’s biggest secrets.”

Lichtblau goes on to give much further detail about exactly the ways in which the Times met the demands of the US government. Though the Times had the information (and thus, you’d think, the bargaining chip), newspaper editors were called into the White House for a meeting, and not the other way around. Government officials repeated all the usual terrorism-is-imminent mantras they use to scare off investigative reporting into their secrets, and, Lichtblau writes, “The clichés did their work; the message was unmistakable: If the New York Times went ahead and published this story, we would share the blame for the next terrorist attack.”

He writes of the media’s misgivings:

in the first few years after 9/11, stories that have now become frequent front-page fodder—about water-boarding of terrorism detainees and other aggressive interrogations tactics, about CIA “black site” prisons overseas, or about covert eavesdropping or other surveillance programs that stretched the limits of the law—simply didn’t get written by most of the mainstream media. If we had known about them, which in most cases we didn’t, there would have been a reluctance to publicize them in those early days of the war on terror.

Nevertheless, Lichtblau says he grew skeptical of the administration, even picking up a reputation as its toughest critic.

In 2005, Jim Risen considered putting information about the wiretapping program into his book, and so began re-reporting the story. When talking to old and new sources, he and Lichtblau discovered something new:

The image of a united front we’d been presented a year earlier in meetings with the administration—with unflinching support for the program and its legality—was largely a façade. The administration, it seemed clear to me, had lied to us.” [Therefore,] the only real question now was not whether the story would run, but when.

There, perhaps unwittingly, Lichtblau reveals that the Bush administration essentially directed the Times’ coverage the whole way. The story was nearly put out of their minds for good, but the administration at least pushed it far away from the election and gave themselves a full year to prepare for the fallout, which is about as good as any democratic government could ask for in an obedient press.

The Times has clearly tried to brush this little embarrassment under the rug, no matter how much it resonates with readers and prospective sources alike.

When current public editor Margaret Sullivan revisited the episode in 2013, everyone involved at the Times absolved themselves of any wrongdoing, blaming the post-9/11 climate and the Bush administration’s lies, learning virtually no lessons.

Bill Keller, then-executive editor and perhaps most responsible for the withholding, is completely guilt-free and particularly incurious:

“Three years after 9/11, we, as a country, were still under the influence of that trauma, and we, as a newspaper, were not immune,” Mr. Keller said. “It was not a kind of patriotic rapture. It was an acute sense that the world was a dangerous place.”

Sullivan wonders,

What would happen now? What if Mr. Snowden had brought his information trove to The Times? By all accounts, The Times would have published the revelations — just as it did many WikiLeaks stories.

Well, “many” of them, yes, but in redacted form, not all of them, and not in an ultimately unredacted, searchable format as WikiLeaks has.

When Chelsea Manning called the Times to bring the original trove that later made its way to WikiLeaks, she said that she left a voicemail with the public editor, but no one called her back.

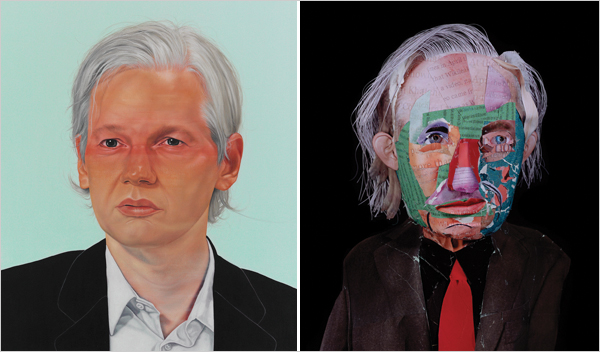

Furthermore, when the Times did publish Manning’s documents in coordination with WikiLeaks, it accompanied its coverage with tawdry, distracting hit pieces on WikiLeaks’ editor Julian Assange. Bill Keller’s now-notorious profile of Assange quotes Times reporter Eric Schmitt as saying, “He was alert but disheveled, like a bag lady walking in off the street, wearing a dingy, light-colored sport coat and cargo pants, dirty white shirt, beat-up sneakers and filthy white socks that collapsed around his ankles. He smelled as if he hadn’t bathed in days.” Hard-hitting stuff. (My letter to the editor challenging the profile was published online but unreturned.)

As FAIR’s Steve Rendall told me back in an interview about WikiLeaks in 2010, he found those very cables to show the Times’ reporting to be lacking:

…the New York Times had taken a cable that they had not published at the time and was not published at the time, and completely misconstrued it, to say that with confidence that Iran had medium-range missiles. That cable once it came out was very useful because it showed the New York Times had way overstated what the cable said.

The cable did not in fact say what they said it said, and in fact included caveats to the effect of the Russian government, Russian intelligence, saying they had looked at the materials and that their assessment was that while Iran may have gotten some pieces of missiles, some spare parts from some medium range missiles, they did not think they had medium-range missiles.

When I asked Rendall about the Times’ motives in being so servile, he said, in part:

The [motive is the] same as it was in publishing story after story selling the Iraq war.

…

It’s the same reason they’re part of an establishment; the media part of that establishment is funded by advertising. Those advertisers are plugged in to the establishment, often large political contributors, many of them are military contractors, or otherwise engaged in business with the government. It’s part of the military-industrial-media complex; the New York Times is central to that.

…

There are all kinds of reasons why the New York Times is an echo chamber for the most powerful official and his policies.

The Times editors write today, “The Times’s commitment is to its readers who expect, and rightly deserve, the fullest, most truthful discussion of events and people shaping the world. … A confident regime that considers itself a world leader should be able to handle truthful examination and criticism.” But clearly that principle only applies to the world leader on the other hemisphere, where the Times feels safe to lob criticism. With a leading paper whose editors are swayed by propaganda, engulfed in fear in a pro-war climate, and who bend to its will even after discovering widespread abuses, the regime back home is likely remaining confident.

Update, 11/13/14: The New York Times‘ public editor Margaret Sullivan recapped responses to the Times‘ editorial, including mine:

On Twitter, some raised another objection – that The Times hasn’t always aggressively pushed back against its own government. Nathan Fuller wrote:

The Times hasn’t been flawless in that regard, it’s true; and I’ve written about that here. But this affirmation of the courage it showed in publishing the Pentagon Papers – and more recently with its publication of the information released through Edward Snowden – is welcome.

I appreciate the inclusion and the response. But I have to push back, again — “hasn’t been flawless” is not critical enough. For the Times to applaud itself explicitly for refusing to bend to American government pressure over the publication of secret government eavesdropping is to pretend its most famous withholding in the last decade, if not several decades, never happened. The Times should be lauded for reporting on Snowden’s documents — though they do not publish the documents themselves in full, and they would not have released the names of the countries where the NSA records and stores nearly all the domestic and international phone calls as WikiLeaks has done.

More to the point, as Sullivan herself acknowledged in her retrospective last year, the fact that the Times sat on the warrantless wiretapping story at the Bush administration’s request was a major reason that Snowden chose to give documents to Laura Poitras, Glenn Greenwald, and Barton Gelman, and not to the New York Times.

C of Lagos, before representing Nigeria U-17 squad

that took part in the 1989 FIFA U-17 World Cup held in Scotland.

Click here to watch live Australia Kangaroos vs New Zealand

Kiwis Rugby Live Streaming below this link. In NASCAR the difference is so pronounced that

you can have a 10-second gap ahead of the pack with one setup, and be

struggling to be at the back of the pack and having spent tires with the other.

LikeLike

For the reason that the admin of this web page is working,

no doubt very soon it will be well-known, due to its

feature contents.

LikeLike

PPG will also outsource its products to other factories to

7 days for a Stock Turnover cycle, save a lot of inventory

and logistics costs. Institutional business capital ‘ These are managed funds willing to invest

in new businesses displaying excellent potential for growth.

Another alternative may be the reorganization of a portfolio company.

LikeLike

They even changed the HTML of the web pages to achieve a good rank for the page.

How well your content is organized makes it easier or harder for the

search engines to find and recommend you as the most relevant to a given keyword phrase.

Shows the way of competition nothing to say just as a website.

LikeLike